The below newsletter was released on January 5, 2021 to the SHIUR community. On January 5, the newsletter was discussed in the weekly virtual SHIUR on zoom with Micki Weinberg and special guest, Emily Jocks of the Mohawk Nation.

SHIUR New World Symphony Newsletter by Micki Weinberg

The current Corona second wave resurgence has, for many of us, shifted the way we think about our relations with others. For most of us, the situation is troubling and murky. All we can do is, is focus on managing our relations with each other. When it comes to corona-risk, we’ve learned that what matters is the form/nature of our relation. We are learning to think in terms of how we relate, making decisions about whether to meet via zoom rather than real life, to go for a distanced walk rather than sitting next to one another, and so on. What effects does this new way of thinking about how we relate with each other have on us? How does shifting the weight towards the medium and the “how” we communicate transform our thought processes and ways of seeing life?

Helmut Newton. Heather Looking Through A Keyhole. 1994. Photo source

In 2016 the American theorist Donna Haraway wrote:

“Trouble is an interesting word. It derives from a thirteenth-century French verb meaning ‘to stir up,’ ‘to make cloudy,’ ‘to disturb.’ We…live in disturbing times, mixed-up times, troubling and turbid times. The task is to become capable, with each other in all of our bumptious kinds, of response…The task is to make kin in lines of inventive connection as a practice of learning to live and die well with each other in a thick present.”

(Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, p1)

Haraway explains “kin” to “mean those who have an enduring mutual, obligatory, non-optional, you-can’t-just-cast-that-away-when-it-gets-inconvenient, enduring relatedness that carries consequences.” (https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/making-kin-an-interview-with-donna-haraway/)

Both of these lines (the latter from December 2019) are incredibly relevant today. We must be inventive in how we connect, in how we relate with one another, and that inventiveness will determine unforeseen ways of how we organize our world and set up our senses of self, community, and more. What new ways have you devised in how you relate to both the human and nonhuman world? Think about everything from washing your hands after touching a door handle to ordering online to zooming in with friends and so forth.

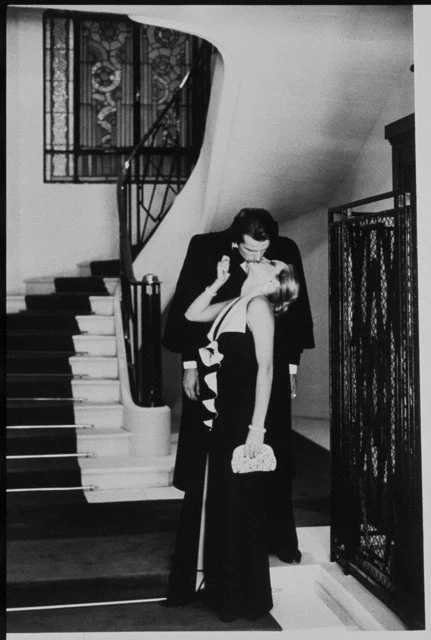

Helmut Newton, The Kiss, 1975. Photo source

As we become conscious and aware of the changes that we are going through and their subsequent effects, we might also find ourselves feeling depressed or suffering from a suffocating sense of limitation and blockage. Can this be a product of a limited and obsolete form of how we construe life?

The British anthropologist Marilyn Strathern argues that:

“[a]wareness takes shape against previous experiences, earlier positions, interests formulated for other purposes and other contexts. Thus (new) ideas are thought through other (old) ideas.” (Reproducing the Future, 1992, p4-5)

New ideas are thought through old ideas! Are we too focused on the dead wood that we forget that there is a new sapling growing out of it? And, if we stay with metaphor, there comes a time, when the sapling is independent enough, that we need to clear the ground, for it to grow on its own.

In other words, as Strathern writes, “Finding a place for new thoughts becomes an act of displacement.” (Ibid, p6)

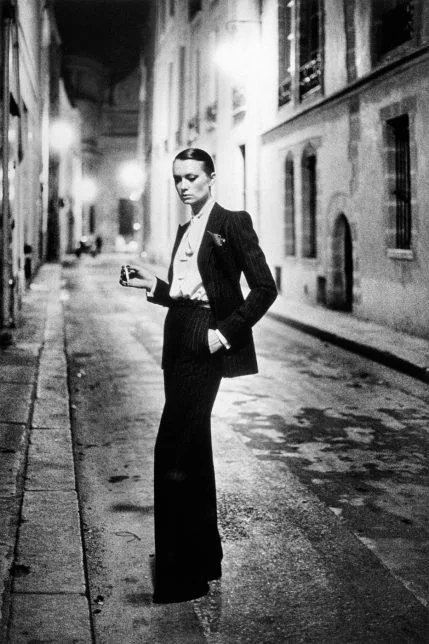

Helmut Newton, Rue Aubriot, 1975. Photo source

Are we at a point where we ought to give new ideas, new forms of living, more space? How can we do this? Sometimes, the old ways of thinking appear and feel deeply entrenched.

For Strathern “it matters what ideas one uses to think other ideas (with).” (Ibid, p10).

Indeed, oftentimes we come with the “wrong” ideas into a situation, and suffer immensely. When we clarify our thinking and perspectives, and attune them better to the needs and the demands of the situation, we find that many of the “problems” we previously had were tied to the wrong ideas we came with.

Haraway comments on Strathern:

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories. Strathern wrote about accepting the risk of relentless contingency; she thinks about anthropology as the knowledge practice that studies relations with relations, that puts relations at risk with other relations, from unexpected other worlds.” (Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, 2016, p12)

Can we apply this to ourselves? Can we be our own anthropologists of the Strathern type, that, in our self-study, relate with ourselves from a situated, dynamic, always changing sense of “self”? Can we attempt to be deeply aware of the structures and their situatedness that we use to mediate life and self? Indeed, Corona is training us quite well in being sensitive to these modes of how we relate!

Minority cultures, especially those with a highly assimilated population, are constantly aware of how the ideas and ways in which we construe and interpret content significantly affect the content itself (again, if we want to seek another parallel from Corona times, we might say that are learning to be very aware of the wifi connection as well as what instrument we use to mediate the call before we even consider who is on the other side—for example, we might see an incoming call, and say we’ll call back when we’re at home with our computer and wifi).

A photo from my great grandmother, of Native American neighbors of the Sioux tribe, in South Dakota (believe it or not, my great grandparents were yiddisher cowboys!)

Native American tribes face a challenge in passing down native content to a generation that has been (forcibly) assimilated, and who might receive the content differently.

In the words of the Mohawk elder Tom Porter:

…we came back...to revitalize our traditions. What we’re trying to do here is to set the foundation for a spiritual mindset. If you’re going to talk about a traditional way of understanding, then you can’t view it the way a European views it; you can’t hear it the way a European hears it. You have to have a mind that has been trained how to interpret the life forces in the world that we live in, in a way that is very different from the European way.” (http://www.fourdirectionsteachings.com/transcripts/mohawk.pdf)

Practice:

For this week, explore “untying knots” of thinking patterns and the idea-strings that make up your mind-quilt (if we want to stay with a Mohawk metaphor).

Carla Hemlock. Turtle Island Unraveling, 2014. Cotton quilt and glass beads. Collection. Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art. (Source: Jennifer McLerran. “Difficult Stories: A Native Feminist Ethics in the Work of Mohawk Artist Carla Hemlock.” Feminist Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, 2017, pp. 68–107)

To help us with this task, we can return to quote from the Medieval wondering Zaragoza born kabbalist Avraham Abulafia (1240-ca.1291) that we explored in April (see it in a different context in newsletter from April 2: Ce Mortel Ennui/ This Deadly Boredom).

Gershom Scholem (1897-1982) writes that “Abulafia’s aim, as he himself has expressed it, is “to unseal the soul, to untie the knots which bind it.’ ‘All the inner forces and the hidden souls in man are distributed and differentiated in the bodies. It is, however, in the nature of all of them that when their knots are untied and they return to their origin, which is one without any duality and which comprises the multiplicity.’ The ‘untying’ is, as it were, the return from multiplicity and separation towards the original unity.” (Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 1941, p131)

How does this text look after reading the ideas of Strathern and Haraway? How is the text different?

Scholem explores the language of “untying knots”:

“What does this symbol mean in Abulafia’s terminology? It means that there are certain barriers which separate the personal existence of the soul from the stream of cosmic life... As the mind perceives all kinds of gross natural objects and admits their images into its consciousness, it creates for itself, out of this natural function, a certain mode of existence which bears the stamp of finiteness. The normal life of the soul, in other words, is kept within the limits determined by our sensory perceptions and emotions, and as long as it is full of these, it finds it extremely difficult to perceive the existence of…things divine. The problem, therefore, is to find way of helping the soul to perceive more than the forms of nature, without it becoming blinded and overwhelmed by the divine light…All that which occupies the natural self of man must either be made to disappear or must be transformed in such a way as to render it transparent for the inner spiritual reality, whose contours will then become perceptible through the customary shell of natural things.” (Ibid, 131-132)

What is missing in Strathern and Haraway that is present in Gershom Scholem’s reading of Abulafia?

When you “untie knots” you will inevitably be bound up in new strings of thoughts and ideas. What do you want to be a part of?

Read:

“The Name” by Don Marquis (1878-1937) in Dreams and Dust,1915, p9-10

Here is the opening stanza:

“It shifts and shifts from form to form,

It drifts and darkles, gleams and glows;

It is the passion of the storm,

The poignance of the rose;

Through changing shapes, through devious

ways,

By noon or night, through cloud or flame,

My heart has followed all my days

Something I cannot name.”

As you read the poem, think about the paradox of his textured descriptions filled with “names” and his de-naming of that which he sees laying behind it all.

Watch:

In the past, we’ve explored films from Cocteau, Bresson, Tati, and now we’ll look at Samurai Cop (1991) written and directed by Amir Shervin.

This poorly made attempt of an action film has achieved cult status in the category of “it's so bad that it’s good.” Whilst it is funny to watch, for our purposes, it’s interesting to explore how the film reflects an outsider’s (the director was an immigrant from Iran) perspective of how Americans speak and communicate, how they relate with one another, and so forth. As you watch it, think about what “ideas” made this film, and what ideas you, as the viewer need to enter with, in order to appreciate it.

This week’s newsletter is named after Antonin Dvorak’s New World Symphony. After listening to the symphony, listen to Leonard Bernstein’s analysis of the composition where he argues that the composition is “A New World symphony from the Old World…let’s not expect it to be American or to point the way for American composers…”

Is Bernstein correct? Or was Bernstein using old ideas in how he interpreted the new ideas of Dvorak?

I look forward to see you all on Wednesday, where we will have a special presenter from the Mohawk nation.

Best regards!

Micki